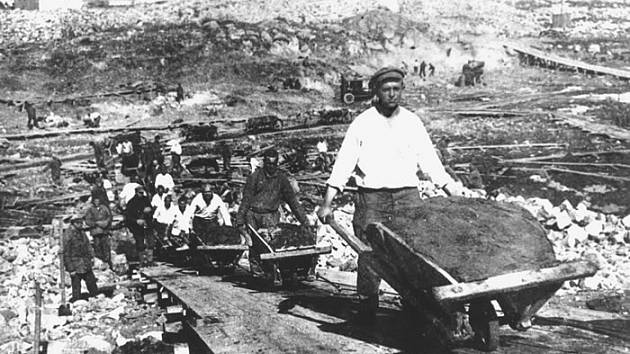

The term „Gulag“ was originally a shortened name of a Russian organization „Glavnoje upravlenje lagerej“ (Main Camp Administration), that ,between the years 1930 – 1960, administrated a giant complex of work, transit, felon and children camps. In a figurative sense, it became a synonym of all the prison system on the territory of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

The entry of the Red Army into central Europe in autumn of 1944 did not just mean liberation from the German occupation. With it also came a wave of mass arrests and deportations into soviet work camps. When the battlefront moved into our (Slovak) territory (6 October 1944), the authorities of the political police of the USSR started arresting and deporting citizens into work camps. Similarly, Russian emigrants and their relatives were also forcibly abducted from Czechoslovakia.

There is an official list of 7 422 abducted Czechoslovak citizens, most of which are citizens of Slovakia. Over 200 of them were women. However, according to the newest information from 2017 approximately 39 000 of Czechoslovak citizens were abducted.

It is not known who gave the order to the security authorities of the USSR to start deporting and what its content was. The act of arresting and deporting itself was performed by the authorities of NKVD („Narodnyj kommisariat vnutrennych del“– national interior commissariat) without the participation of Czechoslovak authorities, even though the agreement concerning the relations between the Czech management and soviet high command after the entry of the soviet armies into Czechoslovakia reached on 8 May 1944 in London, established the Czechoslovak government and its executive and juridical branches as the only authority regarding the fate of the Czechoslovak citizens. In practice however, things were different. NKVD decided on its own, what happened to each „liberated“ Slovak citizen, i.e. who will not be deported and who will be dragged to do slave labour to GUPVI camps (main administration for matters regarding war captives and the interned – Glavnoje upravlenje po delam vojennoplennych i internovannych).